“Indie blockbuster franchise” is not an oxymoron

Friday | May 25, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

The Cannes Film Festival continues even as I type. Much of the wheeling and dealing at the market that accompanies the festival is being driven by two franchises that few people outside the film industry think of as independent films: the Twilight and Hunger Games series. Indie blockbuster franchises aren’t common. In fact, there had previously been only one, but its parallels to these contemporary franchises reflect a recent major shift in international independent distribution.

True or false, The Lord of the Rings is an indie film

In May of 2001, I, as a Tolkien fan since high school, was resolutely ignoring the production of a film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, going on in New Zealand. The first part of the trilogy was to be released in December, and there was widespread skepticism in the press, both popular and trade, and among fans and industry insiders concerning the possibility of the film’s being a success. Another fantasy adaptation, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, looked likely to be the hit of the Christmas season, eclipsing New Line Cinema’s expensive gamble.

Then came New Line’s Cannes event of 2001. Over a three-day weekend, the studio presented an elaborate program to reveal the film. On Friday night there was a screening of a 26-minute preview of footage from all three films, with an extended portion of the Mines of Moria scene in nearly completed form as its centerpiece. Even cast and crew members present, as well as top New Line officials, had not yet seen any of the film’s finished footage until that screening, and they were overwhelmed. Jaded reporters cheered and asked to have the preview re-run. Extra screenings had to be arranged. A series of press interviews were held, and a lavish party complete with sets and props from the film was held in a chateau. Suddenly the popular press was full of infotainment pieces predicting that the trilogy would be a blockbuster hit. Fan webmasters invited to the event posted enthusiastic, even ecstatic reports.

Variety’s report of the preview screening is the first article about the film that I remember reading. It began:

It’s hard to imagine a more relieved group of distribs gathered into one place than the collection who’d just finished watching a 26-minute film from New Zealand that cost $270 million.

The enthusiastic response from distribs, exhibs and worldwide press to the screening of footage from New Line’s “Lord of the Rings” at Cannes Olympia theater means that foreign companies that bet the farm on the three-year franchise now have cause for confidence they’ll recoup their investment–with coin to spare. […]

In marketing meetings after the screenings, NL execs told distribs that the target is for all of them to outdo the previous top grosser in their territory. In some countries, that’s going to mean spending as much again on P&A [prints and advertising] as they did to buy the films in the first place, but at least now that seems more like an opportunity than a terrifying risk.

Rolf Mittweg, at the time head of New Line’s international marketing and distribution, noted: “My Japanese distributor said he had a knot in his stomach for the whole year, and now it has dissolved.” [Adam Dawtrey, “Will ‘Lord’ ring New Line’s bell?” 21-27 May 2001, pp. 1, 66.]

This considerably intrigued me, and it was probably the first step in the long path that ended with me writing The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood.

What Variety was referring to, it turned out, was the twenty-six independent distributors from various territories around the world who were forced by New Line, if they wanted LOTR, to pay large sums up front for the film, sight unseen. That in itself wasn’t odd, since independent films were commonly financed in part by pre-sales to international distributors, often on the basis of a script or a star attached to the project. The difference here was that the chosen twenty-six had to pay a lot (as much as $8 million for the larger European territories) for all three feature-length parts of the film. If the first one flopped, the second and third would be almost worthless. Small wonder they were nervous going into the Cannes event.

As everyone knows, LOTR went on to enormous success, with the third installment becoming only the second film to cross a billion dollars in worldwide grosses (the first having been Titanic in 1997).

Many people would be surprised to learn, however, that LOTR was not the product of one of the major Hollywood studios. It came from an independent company, New Line. True, New Line was at that point owned by Time Warner, but it operated as an independent film producer-distributor. That is, it didn’t receive financing for its films from its parent company but through pre-sales–pretty much the definition of an indie establishment. It was also a studio that thrived in part because it stressed franchises, notably the Nightmare on Elm Street, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Rush Hour, and Austin Powers films. Successful though these were, LOTR was a step up for New Line, both in terms of prestige and budget. It was perhaps the first indie blockbuster franchise.

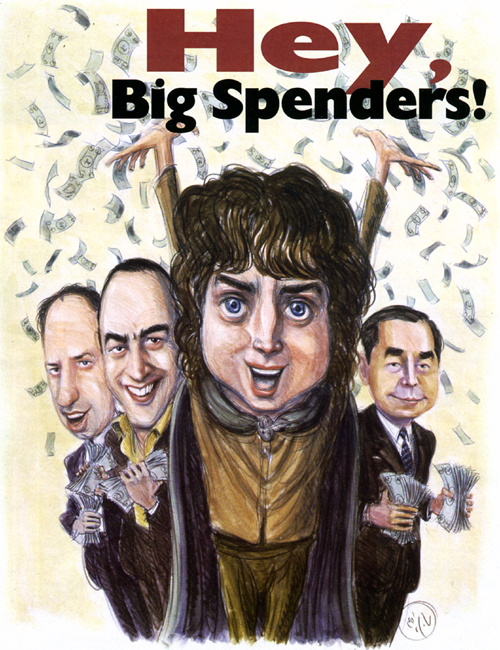

It was such a blockbuster, in fact, that LOTR helped pull the international independent and foreign-language film market out of a major slump that had begun in mid-2000 in the wake of over-production in the late 1990s. The crises in the Brazilian and Argentinian economies in 1999, the bursting of the dotcom bubble in mid-2000, and the 9/11 attacks in 2001 worsened the decline. I won’t go into detail here. (You can read a more thorough account in Chapter 9 of my book.) Suffice to say that the crisis happened to be at its worst when The Fellowship of the Ring came out in mid-December, 2001. During the first half of 2002, there were slight signs of a recovery, but the accumulating income from the film and also from the summer release of the DVD strengthened it considerably. By the time of the American Film Market in early 2003, The Hollywood Reporter ran the caricature above and declared, “With his quest to save Middle-earth from the Dark Lord, the intrepid hobbit might have helped rescue the annual event from the clutches of a global recession.”

As a result, the lucky 26 distributors were able to buy more at the AFM and other important indie sales venues. Reporting from Cannes, Variety declared, “The global bonanzas of ‘Lord of the Rings’ is playing its part in driving big-budget pre-sales.” Screen International said New Line was “buoying the indie market with The Lord of the Rings.” Sales and pre-sales of indie films were up. Small companies could afford to buy more desirable films than in the past. For example, SF Film in Denmark (a branch of Sweden’s AB Svenska Filmindustri) was able to acquire Million-Dollar Baby, a film that previously would have been beyond its means. A few of these companies also used their LOTR money to produce local films or to open art-house cinemas.

The problem was, the film had only three parts. New Line’s next attempt at a blockbuster franchise would knock the biggest supplier of indie films to foreign distributors entirely out of the market.

The New Line void

On December 7, 2007, The Golden Compass was released, the first in an intended trilogy based on the “His Dark Materials,” a trio of prize-winning books by another English author, Philip Pullman. With a reported production budget of $180 million, the film grossed about $70 domestically, though it managed $372 million worldwide.

On March 28, 2008, four years and four weeks after The Return of the King won eleven Oscars, Time Warner announced that New Line would be absorbed into Warner Bros. Entertainment as a genre unit. Its domestic distribution and international sales activities would be dissolved. The top executives of the international sales wing, Rolf Mittweg and Camela Galano, who had helped put together the enormously complex group of foreign distributors who largely financed LOTR, would soon be out of jobs. The fact that the change came less than two months before the Cannes Film Festival led trade papers to assess New Line’s importance as a supplier to the international independent market and to speculate on what companies might step into the void left by its departure.

(For my own analysis of what the loss of New Line product would mean for the indie market, see “Filling the New Line gap,” from November 6, 2008.)

Shortly after the March announcement, Screen International editor Mike Goodridge looked back at the impact of Peter Jackson’s trilogy on the distributors who released it abroad:

The success of the three films for the international partners cannot be overestimated. Nor can the fact they, more than anybody involved, took a huge risk on the trilogy. The risk paid off. The Greens at Entertainment [UK distributor], the Hadidas at Metropolitan [French distributor] and others genuinely shared in the profits of one of the box-office phenomenons of of the last 20 years. It was the international buyers’ dream. Instead of losing money on studio cast-offs, they had a hefty piece of a trilogy which grossed nearly $2bn outside North America. [“The End of the Line,” 7 March 2008, p. 6.]

Goodridge points out that although The Golden Compass, New Line’s intended first entry in the “His Dark Materials” trilogy, had not done well in North America, its box-office abroad was likely to hit in the region of $300 and speculated that if it did, “Warner Bros. will be hard-pressed to deny production to a sequel.” [p. 8]

This optimistic view generously assumes that Warners would want to reward New Line’s old customers abroad by making the two remaining films in the trilogy despite a possible repeat of the first installment’s lackluster domestic gross. Instead, Jeff Bewkes had no interest in keeping up alliances with those loyal distributors, since by investing in the production of films up front, those distributors got to keep most of the box-office takings in their respective countries. As Bewkes said, “With the growing importance of international revenues, it makes sense for New Line to retain its international film rights and to exploit them through Warner Bros.’ global distribution infrastructure.” (For more on the international implications of the absorption of New Line, see this piece on my Frodo Franchise blog.)

Goodridge quotes San Fu Maltha, head of Dutch distributor A-Film (which had the LOTR trilogy for the Netherlands): “New Line was one of the supplier of major films. For [the distributors,] it was, if not a lifeline, an important source.” New Line films from 2007 that had done well abroad included Hairspray, Rush Hour 3, and The Golden Compass. Earlier hits had been entries in the franchises that had traditionally driven New Line’s success: the Austin Powers series, the Nightmare on Elm Street series, and so on. Goodridge concluded that Summit and Overture would be major sources of quality films for the foreign market.

In early May, 2008, with Cannes looming, Variety ran a story about the opportunities opened by New Line’s departure from the market. The subtitle suggests how big the change was perceived to be: “Opportunities Rock: Fresh contenders eager to join international indie scene’s new world order.” The story speculated on the various independent sales groups that will be at Cannes and which ones might be strong enough to replace New Line: QED, with W, District 9, and A Perfect Getaway; Essential Entertainment, with My One and Only; The Film Department’s Law Abiding Citizen and The Rebound.

Swart also noted changes in two major suppliers to the indie market. Summit was growing, having opened its own domestic distribution wing. It “is chasing studio ambitions, which seems to have taken the main emphasis off foreign sales.” Mandate (notable for Juno and the Harold and Kumar sequels) had been acquired by Lionsgate in September, 2007.

Cannes also provided the occasion for a second in-depth analysis of the New Line void by Screen International. Author John Hazelton suggested that New Line’s regular supply of six to eight films to its regular distributors overseas benefited international indies as a whole:

Many sales executives, in fact, go further and suggest that by boosting the fortunes of the distributor partners with which it had ongoing output or package deals—companies including the UK’s Entertainment, France’s Metropolitan, Australia’s Village Roadshow and Spain’s Tri Pictures—New Line effectively elevated the independent international industry as a whole. Other sellers benefited, for example, when the New Line distributors reinvested profits from The Lord Of The Rings and Rush Hour movies—or from last Christmas’ The Golden Compass—in the acquisition of non-New Line films.

Hazelton quotes Steve Bickel, president of The Film Department’s international wing: “New Line provided a great service to all of us because they helped make strong companies that we’re now able to sell to.” The author also presciently singles out Summit and the newly merged Lionsgate and Mandate as “leading the field of remaining big picture suppliers,” noting that both companies had recently expanded into domestic distribution and were signing output deals in some foreign countries.

The article refers to The Weinstein Company and The Film Department as promising new players. Relativity, having produced Atonement, Evan Almighty, Baby Mama and Pineapple Express, was moving for the first time into international sales at Cannes. Other companies are mentioned as possibilities. Hazelton concludes:

On its own, Relativity probably will not fill the gap created by the disappearance of New Line from the business that A Nightmare On Elm Street, The Mask and The Lord of the Rings helped build. And neither will any of the other sales companies or producers now eyeing the fresh demand for upscale product from international buyers. But between them, the new entrants, growing boutiques and established players will be trying fill the New Line-shaped void appearing on the international sales landscape.

Reporting that autumn on the American Film Market, Screen International noted that The Weinstein Company had sold five films to Entertainment, formerly supplied by New Line. These included The Reader, Zack And Miri Make a Porno, and Piranha 3-D. Relativity had closed multi-year output deals with several overseas distributors, including former New Line customers Village Roadshow (Australia, New Zealand, and Greece) and Alliance Films (Canada). Neither company, however, would be the one to release the second indie blockbuster franchise.

From New Line to New Moon

In 2008, the world was in a global recession brought on by the financial crisis of 2007. But even as the trade press was speculating on which company or companies would replace New Line, help was on the way. Summit’s release of Twilight came in November of the same year, and although it did not make as much as the three following films in the franchise so far released, it grossed nearly $393 million internationally, $200 million of that outside North America. A healthy take for a film reportedly budgeted at $37 million.

The modest title did not indicate that Twilight was the launch of a franchise, though obviously Summit was hoping that it would be. The subsequent entries were more forthright and more lucrative: The Twilight Saga: New Moon (November, 2009, nearly $710 million worldwide), The Twilight Saga: Eclipse (June, 2010, about $700 million), and The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn Part 1 (November, 2011, just over $705 million), with the final installment due out in November of this year.

On the occasion of the second film’s release, Mike Goodridge of Screen International noted that the franchise’s success echoed that of a certain earlier series:

Distributed in major territories by companies which had signed to output deals with Summit Entertainment for its in-house productions, the first film, Twilight, was a sensation buyers were hardly anticipating when they made the initial deals. [….] Seeing E1 Films take nearly $20m in the UK, SND in France scoring $17m, Eagle in Italy $14.3m and Aurum in Spain $13.7m last weekend brought back the heady days of The Lord of the Rings openings.

Goodridge also pointed out:

What The Lord of the Rings proved and the Twilight Saga reaffirms is that this kind of independent success is good for everybody. The Twilight distributors will have more money to invest in financing and acquisitions, benefiting other independent productions, while sales companies struggling to get films off the ground in a turgid distribution world will hopefully encounter a renewed buoyancy in the international markets.

He concluded, “For independents, the loss of New Line wasn’t as damaging as first imagined.” [“New Moon’s new line of success,” ScreenDaily.com, 26 November 2009.] It should be pointed out, though, that the gap between the third LOTR film and the first Twilight one was six years.

The Lionsgate share

On January 13, 2012, Lionsgate finalized its deal to buy Summit, thus acquiring the Twilight series. On March 23, Lionsgate released The Hunger Games, with an opening weekend of over $152 million domestically and a worldwide gross of $637 million after 9 weeks in release. Within less than three months, the company came to control the two largest indie franchises since LOTR. In late March, a financial analysis of Lionsgate by The Hollywood Reporter remarked, “The rest of the Hunger Games movies will now bring in significantly higher returns.” [Alex Ben Block, “How ‘Hunger Games’ Box Office Haul Impacts Lionsgate’s Bottom Line,” The Hollywood Reporter, 3 March 2012.] The reference was to the sales of foreign distribution rights, not higher box-office grosses.

Given how recent these events are, it happens that only two international distributors control both the Twilight series and The Hunger Games for their respective territories: Paris Filmes, of Brazil, and Nordisk Films, Denmark. Peter Philipsen, general manager for independent films at the latter told Variety that such series are rare: “There are not a lot of franchises in this business that really work, let along in the independent market,” Philipsen notes. “The last one before ‘Twilight’ was ‘Lord of the Rings,’ which was huge and gave a really big boost to the business as a whole.” [Diana Lodderhose and Adam Dawtrey, “International buyers eye bigger pics,” Variety.com, 5 May 2012.]

If Twilight helped ease the pain of the global recession for many indie distributors worldwide, by Cannes, 2012, the accumulating impact of its franchise and the addition of The Hunger Games led to greater prosperity. Those films and other successful non-franchise movies (some presumably bought with money from the Twilight franchise) led foreign distributors at this year’s Cannes festival to look for bigger films. Diana Lodderhose and Adam Dawtrey reported in Variety:

Sales agents brought a number of well-received big-budget projects to market last year, notably “Cloud Atlas,” “Pompeii” and “Enders Game.” But this year, with the indie sector stronger theatrically than it has been in years, and with international distributors flush with success from pics like the “Twilight” franchise and “The Hunger Games,” as well as “The Iron Lady,” “The Woman in Black,” “The Artist” and “Midnight in Paris” all having performed well territorially, there’s a feeling among buyers that bigger is better.”

A large number of new indie companies have emerged, many of them started by executives formerly at Summit, Lionsgate, and New Line. Among those represented at Cannes for the first time this year is Speranz13 Media, headed by Camela Galano, mentioned above as having helped arrange pre-sales for LOTR at New Line. Variety commented:

Pre-Cannes, a raft of new sales outfits headed by esteemed execs […], coupled with more money in the pockets of indie distribs who had successful runs with such pics as the latest “Twilight” installment, “The Hunger Games” and “The Intouchables,” suggested that this would be a market with greater liquidity.

And it has been.

“Many indie buyers have money now and they know what they want, which is studio-level movies,” said Foresight’s Tama Stuparich de la Barra, whose projects “Lone Survivor” and “Motor City” sold out at the market. [Diana Lodderhose and Dave McNary, “Cannes market totes up solid business,” 21 May, 2012.]

One notable aspect of all this is a return to pre-sales for financing big independent films. A few years ago, pre-sales were declared dead, partly because distributors couldn’t afford to invest in unmade projects. Lionsgate, however, financed about 60% of The Hunger Games through the sales of individual foreign sales rights. Production rebates from North Carolina kept the film’s budget at a relatively modest $80 million, limiting the studio’s risk on the film. These strategies are similar to what New Line tried while making LOTR.

I have yet to see coverage of Cannes that explicitly dubs Lionsgate the successor to New Line, the new indie “mini-major” that will supply a steady stream of films to foreign distributors with which it has output deals. Still, the conclusion seems all but made. At Cannes it began pre-sales for Catching Fire, the sequel to The Hunger Games. On May 23 it announced a long-term renewal of its partnership with the powerful French producer-distributor StudioCanal, including a deal for StudioCanal to distribute Catching Fire in German-speaking regions. Under this partnership Lionsgate has certain distribution rights to StudioCanal’s huge library of film and television titles, the third largest in the world, including titles ranging from Grand Illusion and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie to Terminator 2 and The Deer Hunter. [Dave McNary, “Lionsgate, Studiocanal extend pact,” Variety.com, 23 May 2012] On May 24, Screen International summed how various sales for various companies at Cannes were going:

Patrick Wachsberger and Helen Lee Kim reported a roaring trade on the Lionsgage slate, especially the Dirty Dancing remake. “It has been a strong market for us and the team has been seamless,” Wachsberger said of the post-merger infrastructure. [Jeremy Kay, “Market buoyed by sellouts,” 24 May 2012, p. 1.]

No doubt at some point Lionsgate will face a financial crisis and lose its central status, but with two big indie franchises in progress, it seems settled for the foreseeable future and beyond.

Ironically, the blockbuster franchise that started it all will resume this year, but not in the indie sector. The two parts of The Hobbit, due to be released in December of this year and 2013 as prequels to LOTR, are being produced by New Line. They are not being financed by pre-sales to indie distributors around the world. Instead Warner Bros. is providing funding, and it will also distribute.

I have linked to stories when I could find them online, but some articles I quoted are either behind paywalls or simply not online. They are taken from issues of the trade papers mentioned in the text.

The illustration at the top of the entry topped an article called “Hey, Big Spenders,” cited above. It appeared in The Hollywood Reporter (February 2003), pp. 1, 4, 8, 12. The piece dealt with the American Film Market, which at that time still happened in the spring. Naturally the caricature of Frodo tossing money around caught my eye. (The distributors flush with LOTR cash are, left to right, Joel Pearlman of Roadshow Films, Australia (?); Trevor Green of Entertainment Film Distributors, UK; and Hiromitsu Kurukawa, Nippon Herald Pictures, Japan.) This was one of the few articles I found in the trade press that dealt with the considerable impact that LOTR had on the international indie and foreign-language film market. I used the caricature as an illustration in Chapter 9 of my book. After all, how do you illustrate the concept of a film helping pull the indie business out of a global slump? That picture was ready-made for such a topic. I contacted the artist, Victor Juhasz, for permission to reprint the image, which he kindly gave. It occurred to me that he would be the ideal person to provide an image for the cover of the book as well. Again, how do you illustrate the general concept of a franchise based on The Lord of the Rings? Have a character surrounded by licensed products based on that character, I figured. Fortunately the University of California Press agreed. Based on photos, an action figure, a polystone collectible bust, and a video-game strategy book that I sent him, Victor produced exactly what I had in mind. A small image of that cover illustration appears up at the right, beside the Hollywood Reporter caricature.